The whole gang is here! | Defector

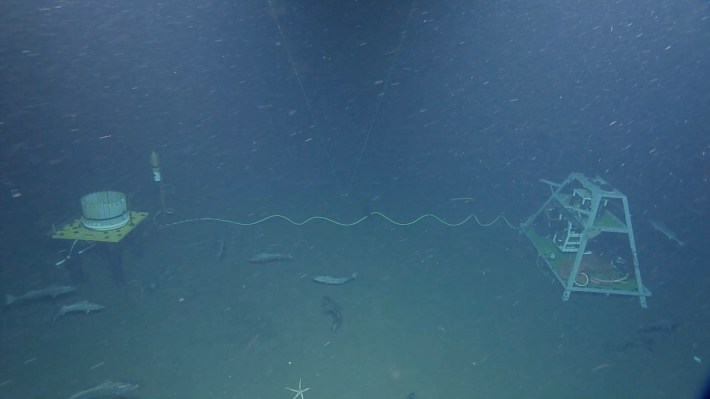

Somewhere on the seafloor of an oceanic canyon near Vancouver Island, scientists in 2022 dropped a bundle of video and audio recording equipment and a carousel loaded with 24 bottles. Each bottle contained a hefty sardine dipped in vegetable oil, and the carousel was programmed to release a sardine every two weeks to attract the deep-sea fish that loiter in the area. The muddy bottom served as a playground for slick shad, noodly eelpouts and hagfish, and flaccid snailfish, all of which roam in near-absolute darkness save for a glimmer of bioluminescence.

Located at a depth of over 600 metres, the observatory is one of many deep-sea observatories set up by Ocean Networks Canada, all of which collect real-time data on the creatures living in the area. The researchers wanted to find out if the fish in the canyon behave differently towards bait when artificial light was on. “Some are attracted, others avoid them,” Héloïse Frouin-Mouy, a marine biologist and bioacoustician at the University of Miami who specializes in marine mammals, wrote in an email. The observatory had both video and acoustic cameras to monitor the fish’s behaviour when the lights were on and off.

Rodney Rountree, a marine biologist specializing in ichthyology at the University of Victoria, was watching the footage when he noticed something strange – “a clawed ‘hand’ coming down from the top of the screen,” Rountree wrote in an email. “That’s all I saw.” To Rountree, the clawed hand looked exactly like the creature from the 1954 film. The horror of the Amazona film he saw as a child. “After a few seconds, however, I assumed it must have been a seal,” he added.

As Rountree watched more videos, he spotted several, increasingly distinctive seals. Some stared directly into the camera as if to show off. The sight of an elephant seal in a deep-sea observatory seemed rare, and he reached out to Frouin-Mouy to see if she would write a brief note about the observation. “I didn’t know that the elephant seals would be so common in this location and that we would learn so much about their behavior,” Rountree said. Her follow-up paper was recently published in PLOS One.

When Frouin-Mouy saw the footage, she was amazed. Northern elephant seals are true giants; males can grow to over 4 metres long and weigh almost 2000 kilograms. When a male reaches sexual maturity, he develops a floppy nose that he can inflate during courtship. His neck thickens to protect him during the many fights with other male seals. But the males Frouin-Mouy saw on screen did not yet have noses. “The footage shows subadult male northern elephant seals, about which very little is currently known,” she said.

Scientists actually know a lot about elephant seals in general, because the mammals are often Scientists themselvesthat swim through the ocean with a biologger or tracking device on their heads. The seals travel enormous distances twice a year, swimming from the beaches of California and Mexico, where they molt and breed, to their feeding grounds in the northern Pacific. And they dive to depths of up to 1,500 meters. However, this research is often assigned to female elephant seals because they are easier to find and handle and have a higher chance of survival. As a result, not much was known about where young male northern elephant seals hunted or what they ate.

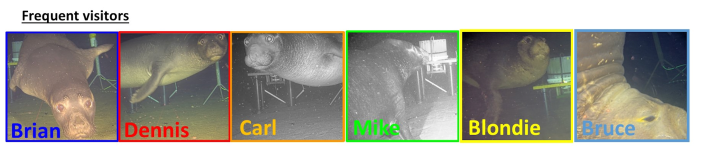

Frouin-Mouy used the footage to identify eight different seal pups, six of which returned to the observatory multiple times. Each seal had distinct body markings and scars, as well as eye pencil-like markings that accumulate around their eyes in the sea. “In a playful nod to where these mammals are most often studied and observed on land, I decided to name them after members of the Beach Boys,” Frouin-Mouy said. So the wandering seals became Brian, Dennis, Carl, Al, Mike, David, Blondie and Bruce. (There was no ninth elephant seal to be named Ricky.)

The seals came to the observatory not for a single sardine, no matter how fat, but for the fish that flocked around the device. “Sablefish and other fish are strongly attracted to structure, so the observatories attract a lot of fish even without bait,” Rountree said. And although some fish fled when the observatory’s LED lights crackled to life, the sablefish were even more strongly attracted to the site. Most of the time, however, the seals spent near the observatory when the sound of the acoustic sonar hydrophone sounded, suggesting that the seals had learned to associate the sonar sound with a feast of fish — as if they hear a dinner bell and swim over to feast.

Seals Al and David, both about six years old, appeared only once. Al arrived in October and David later in December. Mike, a seven-year-old seal pup, was the site’s most loyal visitor, returning nine times over the course of about a month. Many of the videos show the seals hunting shagfish, both successfully and unsuccessfully. One shot shows Dennis inspecting and then ignoring a snailfish, a very gelatinous fish. A later video shows Dennis accidentally catching a snailfish instead of a shagfish, and immediately spitting out the seemingly disgusting morsel. “This is fascinating considering these animals are known to sometimes eat hagfish, even though they have a strong mucus production,” Frouin-Mouy said.

Before Dennis catches the snailfish, it is seen bobbing its head. The observatory recorded low-frequency signals almost every time the seals bob their heads, and researchers speculate that the seals may be making these sounds to scare their prey. Rountree was surprised that none of the snailfish made any noise when attacked or even eaten. Researchers have recorded the sounds of snailfish in captivity, and some have speculated that the fish make such noises in response to threats. “There’s nothing more threatening than an elephant seal chasing you!” Rountree said. “Still no noise.”

Some seals came into view while taking a short nap.

A recent article in Science revealed the extreme sleep habits of northern elephant seals, which fall into a deep REM sleep as they gradually sink to the depths. The seals sleep and sink for about 10 minutes, then swim back to the surface. It sounds scary, but the deep sea is a much safer place for the seals, out of reach of surface-dwelling orcas and great white sharks.

Still, the fact that so many seals were able to find the observatory and return to it is a true navigational miracle. “We are still baffled as to how these seals managed to find such a small place in the vast open ocean, in total darkness and on multiple occasions,” said Frouin-Mouy. The researchers suspect that the seals rely on a combination of tools – listening for acoustic signals from the sonar signal, paying attention to visual cues from the LED, and sensing magnetic fields.

But the videos make it clear that there was good food in the waters surrounding the observatory. Coalfish, which can grow to over a meter long and live up to 90 years, are full of omega-3 fatty acids. They are delicious food for both seals and humans, many of whom also refer to the fish as black cod. Although we dream of it, no human will ever experience the taste of a coalfish as fresh as the one Brian, Dennis, Carl, Al, Mike, David, Blondie and Bruce devoured. But wouldn’t it be nice!